Editor-in-chief of For-Serbia The Website

The Delegitimization Campaign Against Nationalists

Editor-in-chief of For-Serbia The Website

He clasps the crag with crooked hands . . . he watches from his mountain walls, and like a thunderbolt he falls.

He clasps the crag with crooked hands . . . he watches from his mountain walls, and like a thunderbolt he falls.

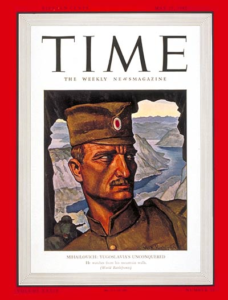

These words, written of an eagle, today are a far better fit for one of the most amazing commanders of World War II. He is Yugoslavia’s Draja Mihailovich. Ever since Adolf Hitler vaingloriously announced a year ago that he had conquered Yugoslavia, Draja Mihailovich and his 150,000 guerrillas in the mountains south-west of Belgrade have flung the lie in Hitler’s teeth. It has been probably the greatest guerrilla operation in history:

Last fall Mihailovich kept as many as seven Nazi divisions chasing him through his Sumadija mountains.

Mihailovich’s swarming raiders have preserved an “Island of Freedom”, which for a time was 20,000 square miles in area, with a population of 4,000,000.

Mihailovich’s annihilation of Axis detachments, bombing of roads and bridges, breaking of communications and stealing of ammunition have been so widespread that the Nazis had to declare a new state of war in their “conquered” territory.

Last October the Nazis even asked for peace.

When Mihailovich refused, they priced his head at $1,000,000.

When the Nazis desperately needed troops in Russia, they tried to leave Mihailovich to the forces of their Axis partners and stooges. But Italian, Bulgarian and Rumanian soldiers could not deal with him, and the Nazis went back. Only last week the Russians announced that a Nazi division had arrived at Kharkov fresh from Yugoslavia—where it had certainly not been stationed for a rest.

Mihailovich’s example has kept all Yugoslavia in a wild anti-Axis ferment. The Axis has resorted to executing untold thousands, but the revolt continues. Last month the Nazis said they had seized Mihailovich’s wife, two sons and daughter, threatened to execute all relatives of Mihailovich’s army and 16,000 hostages if the General did not surrender within five days. He did not. It is a misfortune that conquered Europe cannot learn detail by detail the effective methods used by the gaunt, hard, bronzed fighter on TIME’S cover (painted by one of his compatriots, Vuch Vuchinich—called Vuch, to rhyme with juke). But Draja Mihailovich is completely cut off from the democracies’ press, hemmed in by the Axis forces in Yugoslavia, Rumania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece. His only direct contact with the world beyond has been through smugglers and a mobile radio transmitter which he concealed somewhere in his mountain fastnesses.

Even so, he has already become the great symbol of the unknown thousands of supposedly conquered Europeans who still resist Adolf Hitler. As he watches from his mountain walls, he stands for every European saboteur who awaits the moment to jam the machine, plant the bomb, or pry up the railroad rail. He has directly inspired others, like Rumanian Patriot Ion Minulescu, who harries the Axis from the Carpathians, and Albanian and Montenegrin guerrillas who worry at Italian flanks on the Adriatic coast.

As a legend, Draja Mihailovich will unquestionably live as long as World War II is remembered. How long Draja Mi-hailovich himself will live is highly problematical. Like the heroes of Bataan, the guerrillas of Sumadija cannot be expected to fight forever without reinforcements at least of ammunition and food. Yet the only way these can be furnished at present is by parachute. Both the Russians and British are said to have dropped small amounts. In recent months Mihailovich has begged over the radio for all he can get. Last fortnight London reported that 24 Axis divisions (Germans, Hungarians and Bulgarians) had been sent into the Sumadija mountains to deliver the coup de grace.

Serb

The once-obscure Balkan officer who has thus far successfully challenged the modern world’s greatest conqueror was born 47 years ago in Chachak, Serbia, in the craggy lands which he now clasps. His parents died when he was a child, and he was raised by an uncle, a musical Serbian colonel. Draja Mihailovich plays the mandolin excellently. He entered Belgrade’s Serbian Military Academy at 15. He has been a lifelong soldier, an officer who got his training under fire. He is also profoundly a Serb. For those who know the Serbs, that fact alone would account for his great-hearted defiance.

The blood bath of oppression which for centuries has laved the minarets and green poplars of the Balkans has also watered a glowing military spirit in little Serbia—an unconquerable will toward freedom.

In 1389, a date of horror in Serbian minds, the Turks defeated the Serbs on the plain of Kosovo and slaughtered the cream of Serbian manhood. For the next four centuries Turkey bore down on Serbia as hard as Adolf Hitler has done, with such devices as impaling, mutilation and the roasting of living Serbs on spits.

Yet Serbia continued to resist, helped by Austria or Russia, who valued the Balkans as a buffer against the Turk, or betrayed them if it suited their purposes. Early in the 19th Century the great Serbian King Kara George fought Turkey with Russian aid, got a limited autonomy with Turkish garrisons still in Serbia. But Napoleon’s advance on Moscow drew away Russian support, and the Turks pressed Serbia hard again. This time Serbia’s Milos Obrenovich made a deal with Turkey for recognition. The deal included the assassination of Kara George, and thus started an Obrenovich-Kara George dynastic rivalry that was to continue for decades.

Serbia’s rulers were often personally weak and depraved, but the Serbs in general grew hard and defiant in the schools of Turkish tyranny and European Realpolitik. They never suffered from the flabbiness that comes with ease. In the First Balkan War (1912), Serbia and her Balkan allies finally ousted Turkey.

In World War I a supposedly exhausted Serbia hurled back two Austrian attacks, was ravaged by typhus and gave way before a third, then fought back again from Salonika. Only a year ago a revolution in Yugoslavia, where the dream of Balkan federation was becoming an actual as well as a political fact, deposed the pro-Nazi regent Prince Paul, and Serbian General Dusan Simovich courageously challenged the juggernaut of Adolf Hitler. In Draja Mihailovich’s mountains the challenge persists today.

Soldier

In 1912, at 19, Mihailovich left the Serbian Military Academy to fight the Turks. Wounded the next year, he returned to school as a sublieutenant wearing the Obihch medal for “personal courage.” In 1914 the Austrian attack again broke up school and Mihailovich was again wounded, received the Order of the White Eagle. On the eve of the Salonika offensive he rejoined his company and finally returned to Serbia wearing its highest decoration, the Kara George Star with crossed swords.

After these two laboratory periods in the field, he studied military theory, held various Yugoslavian commands, was active in political bodies for the preservation of Balkan unity. He was sent as military attache to Sofia (1934) and Prague (1936), and is rumored to have been connected with underground movements working against Nazi influence in both Bulgaria and Czecho-Slovakia.

In 1939, as chief of Yugoslavia’s fortifications, he revealed himself as a Balkan De Gaulle, holding that a nation of such limited financial means should not try to build Maginot Lines but should concentrate on mobile and offensive possibilities. His superiors opposed him and he was transferred to the military inspection service.

Presently he submitted a memorandum warning that a pro-Nazi Fifth Column threatened Yugoslavian unity and full mobilization in case of attack. War Minister Milan Neditch, now Hitler’s Serbian Quisling, asked Mihailovich to withdraw his memorandum. He refused, and was sentenced to 30 days of military arrest for “disloyalty.” He was freed at the instigation of Inspector General Bogoljub Illich, who is now in London with the Yugoslavian Government-in-Exile.

Sumadija

When Hitler’s Stukas bombed Belgrade on April 6, 1941, Mihailovich had a coastal command in Herzegovina. As the Nazis overwhelmed General Dusan Simovich’s bravely fighting army, Mihailovich retreated eastward into mountainous Sumadija, where Serbia had long fought the Turks. Thousands of disbanded or unmobilized Yugoslavian troops joined him, bringing their arms and equipment. The force was swelled by peasants and mountaineers.

The Nazi press has reviled Mihailovich’s army as “rebels, Jews and Communists.” Unquestionably they are rebels. Unquestionably some are Jews, some are Marxist Communists of one shade or another. Many more, probably, are Balkan “Communists,” which usually means partisans of the country as against the city, the farmer as against the businessman. These people in general have Slavic, pro-Russian (Tsarist or Stalinist) leanings. The United Nations press has often referred to Mihailovich’s forces as Chetniks —the name of a Serbian patriotic body which long fought guerrilla wars against Serbia’s oppressors. Doubtless many are Chetniks or their descendants. But Mihailovich’s army is best described as a patriotic Balkan force, with a majority of Serbs, built around a large nucleus of trained Yugoslavian troops.

In size, in the long military experience of its leader and the great number of its troops, it dwarfs the forces of such historic guerrillas as the Tirolean patriot Andreas Hofer, the Philippines’ Emilio Aguinaldo, and Mexico’s Francisco “Pancho” (“I’ll use the whole ocean to gargle”) Villa.

Stories

Tales about Mihailovich, apocryphal or smuggled out of his mountains, abound in Yugoslav circles. It is said that he has done some of his own espionage, eating with German officers in a tavern where the host, devoted to him, was panicky with fright. Nazi officers are said to have driven up to a farmhouse where Mihailovich and friends were staying. When he had convinced the Nazis of his innocence, one of his friends remarked: “That was a close one.” Mihailovich replied: “It was close for them, too.” He pointed to a bush behind which a guerrilla machine-gun crew had been ready for the Nazis. The General is also rumored to have done a brisk trade exchanging Italian prisoners for Italian gasoline at the rate of one Italian private for one can of gas, one colonel for 50 cans.

Today Draja Mihailovich seems legendary, but he is a legend with a big basis in fact: the fact that he has kept from five to ten Nazi divisions at a time fighting to conquer the country which they destroyed twelve long months ago.

Time Magazine (1942)

Kissinger on the Siege of Sarajevo

Kissinger lays forward some very thought-provoking views and suggestions on what ought to be done in the Bosnian War to media tycoon billionaire Mort Zuckerman, sitting in for Charlie Rose. They weigh more when you bear in mind that it comes from a man of his importance, who by many is regarded as the most influential American Secretary of State of the 20th century.

Among other things, Kissinger dismisses the notion that the Serbs are separatists in Bosnia and goes on to talk about the West’s bombing of the Serbs and the siege of Sarajevo. In line with this perception of the events in Bosnia, Kissinger suggests that the Serbs as well as Croats should be allowed to join their motherlands.

But whilst looking at the interview, one should not forget that it would have been a whole different story had the now-retired man been in office. A former American statesman himself, Kissinger is by no means a saint. It’s just that now he couldn’t care less about telling the truth, and probably more so when the truth is so obvious.

Noam Chomsky Mocks Intellectuals or ‘Independent Minds’

Chomsky talks about intellectuals who were supporting the bombing campaign against Yugoslavia and comes to the conclusion that they are far from independent minds. All they really do is follow the party lines within some more or less defined boundaries.

David Hackworth Admires Serbian Defiance

Not paying much attention to Shirley Cloyes’ motor mouth, David Hackworth gives his impressions of the Serbian people from this war.

The Albanian Lobby in the U.S. Congress and The Hague

The President of the Albanian lobby on Capitol Hill is first confronted by the Serbian American Congresswoman Helen Delich Bentley for his statements about the Albanians’ situation in Kosovo. After this event we will see a clip from The Hague where the accused Slobodan Milošević talks about the lobby’s role in the Kosovo conflict and the demonization of Serbs in the American public.

Martti Ahtisaari vs. Expert on International Law

Despicable as it sounds, what Martti Ahtisaari is really saying on this occasion of him receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2008, is that he implemented the policies of the same states that bombed Serbia and Yugoslavia in 1999. Or in other words: “we fooled the Serbs into these negotiations and said to the Albanians that they would get independence even if they were to blame for them not coming to a reach acceptable to both parties.” With this being said, the Albanian delegation refused to autonomy higher than any international standard anywhere in the world. This was possible only because the politicians in Belgrade don’t want to rule the Kosovo Albanians, which is a fact they have repeated and made clear but one which Martti Ahtisaari does not mention here. Their interest is only to preserve their country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. But luckily, there are always those who stand up for the truth. David Jacobs, a Lawyer and expert on international law, lays waste to myths such as that Kosovo’s autonomy was revoked in 1989, when in fact Albanians had cultural autonomy on a level higher than many other minorities in Europe. This is illustrated by the fact that they had their own newspapers and other media, without any restrictions from the Serbian authorities whatsoever. The thing was that the Albanian leaders saw it differently. As far as they were concerned, “Kosova” was already an independent state so they had no reason to negotiate with Belgrade. This is where the myth about “underground schools and hospitals” and even “apartheid” originates from. It was only a parallel society that they had created voluntarily, the same way they voluntarily refused to vote in the elections of a country which everyone except the Albanians in Kosovo recognized as a real state with that province as an integral part of that state with its internationally recognized borders.

Despite increasing US influence, the European Community continued its efforts, begun in 1991, aimed at ending the Yugoslav federation through a negotiated secession of the various republics. The EC member states still sought to use the Balkan crisis to affirm the Community’s potential as a global actor. The European Community’s policy of international assertiveness had failed badly in Croatia during 1991, but the Europeans now sought to make up for this failure and to reestablish their diplomatic presence in Bosnia.The continued importance of the Balkan conflict was clear, and is was widely considered “the virility symbol of the Euro-federalists” – a way of establishing the Community as a global player to be reckoned with.

The EC mediation activities were directed by José Cutileiro, a Portuguese diplomat. During February and March 1992, Cutileiro brought together the leaders of the three major groups from Bosnia (including Izetbegović, who represented the Muslims) for a series of international conferences. The EC mediation was predicted on the assumption that Bosnian independence was inevitable, and Cutileiro sought a constitutional arrangement that might defuse ethnic tensions and thus preclude civil war. Cutileiro worked out a plan to divide Bosnia into three separate regions, each of which would possess a high level of autonomy. The central government in Sarajevo would be left with limited powers as part of a confederalized state. Of the total area of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Muslims were to be given effective rule in regions comprising 45 percent of the total, the Serbs would receive 42.5 percent, and the Croats (the smallest of the three groups) would receive 12.5 percent.

The Lisbon agreement, as it became known, was hardly perfect, and it entailed a compromise among all three groups. For the Serbs, it represented some concession with regard to territory. Serbs accounted for less than half the population of Bosnia, and they owned a disproportionate share of the land; the 42.5 percent that they would receive under the Cutileiro plan constituted a reduction in territorial control. From the Muslim side, the entire idea of confederation was a concession. The Muslims effectively controlled the central government, having won the parliamentary elections, and they favored a unified state; they viewed a confederation with a weak central government negatively. From the Croat side, there was surely dissatisfaction that they would control far less territory than the other groups. Significant numbers of each ethnic group would have to live as minorities in areas dominated by another group.

Despite these flaws, the three ethnic groups all agreed to the plan on March 17, presumably because it was better than the alternative, which was war. Crucially, the Izetbegović government also agreed. The possibility briefly emerged that war could be averted through a compromise settlement. The Bush administration, however, opposed the European efforts from the start, and this opposition contributed to the breakdown of the Lisbon agreement. The administration’s opposition flowed from a more basic rivalry between the United States and the European Community, which was growing during this period. With US encouragement, the Croats and Muslims both withdrew from the agreement – effectively reneging on their commitments – Mach 25-26, 1992. The Cutileiro plan was never implemented, and full-scale war commenced within two weeks.

Let us look more closely at the role of US officials and their efforts to undercut the Lisbon agreement. These efforts began with the US ambassador in Belgrade, Warren Zimmermann, who encouraged Izetbegović to reject the peace plan. A New York Times article notes: “Immediately after Mr. Izetbegović returned from Lisbon, Mr Zimmermann called on him…. ‘[Izetbegović] said he didn’t like [the Lisbon agreement],’ Mr. Zimmermann recalled. ‘I told him if he didn’t like it, why sign it?” According to former State Department official George Kenney: Zimmermann told Izetbegović … [the United States will] recognize you and help you out. So don’t go ahead with the Lisbon agreement” (emphasis added. The former Canadian ambassador to Yugoslavia, James Bissett, confirms Kenney’s account. In other words, Zommermann offered Izetbegović a direct incentive – US recognition – in exchange for his rejection of the Lisbon agreement.

US efforts to undermine the plan extended well beyond the US embassy in Belgrade. An official Dutch investigation offered this account: “[Secretary of State] Beker’s policy was now directed at preventing Izetbegović from agreeing to the Cutileiro plan … and informing him [Izetbegovći] that the United States would support his government in the UN if any difficulties should arise.” In addition Baker “urged his European discussion partners to halt their plans” for decentralizing authority in Bosnia. It is interesting to note that the section of the Dutch report that discusses this period is entitled, “The Cutileiro Plan and Its Thwarting by the Americans.” Cutileiro himself later claimed: “Izetbegović and his aides were encouraged to scupper that deal [from Lisbon] by well meaning outsiders.” – which was probably a polite reference to the US activities. According to EC mediator Peter Carrington, the “American administration made it quite clear that the proposalsof Cutileiro … were unacceptable.” Lord Carrington also claimed that US officials “actually sent them [the Bosnians] a telegram telling them not to agree” to Cutlieiro’s proposed settlement. These facts strongly suggest that the United States played a key role during this early period of the Bosnia conflict; later claims of US inactivity in Bosnia are incorrect.

The US strategy was successful in removing the possibility of an EC-brokered agreement early in the conflict. Let us now consider a counterfactual question: Could the Lisbon agreement have prevented war in Bosnia? This must remain one of the key “what if” question of the Yugoslav conflict that can never be answered definitively. The plan was accepted by the three parties only in preliminary form, with many details still to be worked out; whether or not a final agreement could have been achieved – even in the absence of US opposition – cannot be known for certain. Nevertheless, the Cutileiro plan clearly held considerable promise, a point acknowledged by former US diplomats. Zimmermann, for example, admitted in an interview with the New York Times that the Cutileiro plan “wasn’t bad at all.” In his memoirs, Zimmermann goes further and states that the Cutileiro plan “would probably have worked out better for the Muslims than any subsequent plan, including the Dayton formula [that ended fighting in 1995].” And according to Sell, who served in the US embassy in Belgrade, the “Cutileiro plan would have established a more effective Bosnian central government and probably resulted in less of an ethnically divided state than the accord agreed to at Dayton.” The Cutileiro plan had the added advantage that it sought to prevent war; this advantage was not shared by any of the subsequent peace proposals, including the Dayton accord.

Some observers doubt that the Lisbon agreement was viable; since, it is alleged, the Bosnian Serb leaders were not negotiating in good faith; they would never have accepted a compromise agreement. There is no question that the Serb leadership contained several dubious figures, some of whom would later orchestrate serious war crimes. In March 1992, however, before full-scale war had begun, Serb leaders welcomed the Lisbon agreement, and they endorsed it in the strongest terms. Radovan Karadžić, who represented the Serbs at Lisbon, called the agreement “a great day for Bosnia and Herzegovina.” And it should be recalled that it was the Muslims and the Croats, not the Serbs, who actually renaged. There is no evidence that the Serbs were bent on war at this point. Even after Izetbegovć reneged, the Serbs remained open to a compromise agreement similar to the Cutileiro plan. As late as April 1992, “the Serb leaders [in Bosnia] were probably still willing to accept a single state organized into a loose confederation divided into three ethnic ‘cantons,'” according to an unclassified report by the Central Intelligence Agency. A revival of the plan now proved impossible, and war was the result.

Overall, US policy – by pushing for early recognition of Bosnia while undercutting EC mediation – augmented the risks of a wider conflict. These risks were recognized in policy-making circles. Sell writes that in early 1992, “The United States … began to press for recognition of Bosnia, reducing the prospects – low as they might be – that continued negotiations could head off conflict.” Kenney states the mater more bluntly: “The [US] intelligence community was unanimous in saying that if you recognize, Bosnia is going to blow up.” The cronology of events supports the view that US policy helped precipitate violence: On March 27, the day after Izetbegovć withdrew from the Lisbon accord – and did so at the urging of US officials – the Serbs declared their independence from Bosnia-Herzegovina, thus laying the groundwork for war. With US support, Bosnia-Herzegovina seceded from Yugoslavia and then achieved international recognition as an independent state on April 6. The Western European states set aside their reservations and went along with the US position on recognition. Full scale ethnic war also commenced on April 6, thus coinciding exactly with the timing of international recognition. Viewed in retrospect, the US policy during this period must be viewed as a destabilizing force. Just as Germany had played a key role in destabilizing the region in 1991, the United States played the destabilizer in Bosnia in 1992.