He clasps the crag with crooked hands . . . he watches from his mountain walls, and like a thunderbolt he falls.

He clasps the crag with crooked hands . . . he watches from his mountain walls, and like a thunderbolt he falls.

These words, written of an eagle, today are a far better fit for one of the most amazing commanders of World War II. He is Yugoslavia’s Draja Mihailovich. Ever since Adolf Hitler vaingloriously announced a year ago that he had conquered Yugoslavia, Draja Mihailovich and his 150,000 guerrillas in the mountains south-west of Belgrade have flung the lie in Hitler’s teeth. It has been probably the greatest guerrilla operation in history:

Last fall Mihailovich kept as many as seven Nazi divisions chasing him through his Sumadija mountains.

Mihailovich’s swarming raiders have preserved an “Island of Freedom”, which for a time was 20,000 square miles in area, with a population of 4,000,000.

Mihailovich’s annihilation of Axis detachments, bombing of roads and bridges, breaking of communications and stealing of ammunition have been so widespread that the Nazis had to declare a new state of war in their “conquered” territory.

Last October the Nazis even asked for peace.

When Mihailovich refused, they priced his head at $1,000,000.

When the Nazis desperately needed troops in Russia, they tried to leave Mihailovich to the forces of their Axis partners and stooges. But Italian, Bulgarian and Rumanian soldiers could not deal with him, and the Nazis went back. Only last week the Russians announced that a Nazi division had arrived at Kharkov fresh from Yugoslavia—where it had certainly not been stationed for a rest.

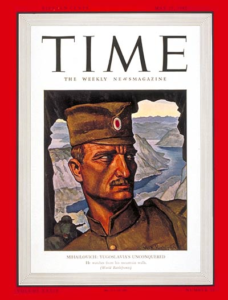

Mihailovich’s example has kept all Yugoslavia in a wild anti-Axis ferment. The Axis has resorted to executing untold thousands, but the revolt continues. Last month the Nazis said they had seized Mihailovich’s wife, two sons and daughter, threatened to execute all relatives of Mihailovich’s army and 16,000 hostages if the General did not surrender within five days. He did not. It is a misfortune that conquered Europe cannot learn detail by detail the effective methods used by the gaunt, hard, bronzed fighter on TIME’S cover (painted by one of his compatriots, Vuch Vuchinich—called Vuch, to rhyme with juke). But Draja Mihailovich is completely cut off from the democracies’ press, hemmed in by the Axis forces in Yugoslavia, Rumania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece. His only direct contact with the world beyond has been through smugglers and a mobile radio transmitter which he concealed somewhere in his mountain fastnesses.

Even so, he has already become the great symbol of the unknown thousands of supposedly conquered Europeans who still resist Adolf Hitler. As he watches from his mountain walls, he stands for every European saboteur who awaits the moment to jam the machine, plant the bomb, or pry up the railroad rail. He has directly inspired others, like Rumanian Patriot Ion Minulescu, who harries the Axis from the Carpathians, and Albanian and Montenegrin guerrillas who worry at Italian flanks on the Adriatic coast.

As a legend, Draja Mihailovich will unquestionably live as long as World War II is remembered. How long Draja Mi-hailovich himself will live is highly problematical. Like the heroes of Bataan, the guerrillas of Sumadija cannot be expected to fight forever without reinforcements at least of ammunition and food. Yet the only way these can be furnished at present is by parachute. Both the Russians and British are said to have dropped small amounts. In recent months Mihailovich has begged over the radio for all he can get. Last fortnight London reported that 24 Axis divisions (Germans, Hungarians and Bulgarians) had been sent into the Sumadija mountains to deliver the coup de grace.

Serb

The once-obscure Balkan officer who has thus far successfully challenged the modern world’s greatest conqueror was born 47 years ago in Chachak, Serbia, in the craggy lands which he now clasps. His parents died when he was a child, and he was raised by an uncle, a musical Serbian colonel. Draja Mihailovich plays the mandolin excellently. He entered Belgrade’s Serbian Military Academy at 15. He has been a lifelong soldier, an officer who got his training under fire. He is also profoundly a Serb. For those who know the Serbs, that fact alone would account for his great-hearted defiance.

The blood bath of oppression which for centuries has laved the minarets and green poplars of the Balkans has also watered a glowing military spirit in little Serbia—an unconquerable will toward freedom.

In 1389, a date of horror in Serbian minds, the Turks defeated the Serbs on the plain of Kosovo and slaughtered the cream of Serbian manhood. For the next four centuries Turkey bore down on Serbia as hard as Adolf Hitler has done, with such devices as impaling, mutilation and the roasting of living Serbs on spits.

Yet Serbia continued to resist, helped by Austria or Russia, who valued the Balkans as a buffer against the Turk, or betrayed them if it suited their purposes. Early in the 19th Century the great Serbian King Kara George fought Turkey with Russian aid, got a limited autonomy with Turkish garrisons still in Serbia. But Napoleon’s advance on Moscow drew away Russian support, and the Turks pressed Serbia hard again. This time Serbia’s Milos Obrenovich made a deal with Turkey for recognition. The deal included the assassination of Kara George, and thus started an Obrenovich-Kara George dynastic rivalry that was to continue for decades.

Serbia’s rulers were often personally weak and depraved, but the Serbs in general grew hard and defiant in the schools of Turkish tyranny and European Realpolitik. They never suffered from the flabbiness that comes with ease. In the First Balkan War (1912), Serbia and her Balkan allies finally ousted Turkey.

In World War I a supposedly exhausted Serbia hurled back two Austrian attacks, was ravaged by typhus and gave way before a third, then fought back again from Salonika. Only a year ago a revolution in Yugoslavia, where the dream of Balkan federation was becoming an actual as well as a political fact, deposed the pro-Nazi regent Prince Paul, and Serbian General Dusan Simovich courageously challenged the juggernaut of Adolf Hitler. In Draja Mihailovich’s mountains the challenge persists today.

Soldier

In 1912, at 19, Mihailovich left the Serbian Military Academy to fight the Turks. Wounded the next year, he returned to school as a sublieutenant wearing the Obihch medal for “personal courage.” In 1914 the Austrian attack again broke up school and Mihailovich was again wounded, received the Order of the White Eagle. On the eve of the Salonika offensive he rejoined his company and finally returned to Serbia wearing its highest decoration, the Kara George Star with crossed swords.

After these two laboratory periods in the field, he studied military theory, held various Yugoslavian commands, was active in political bodies for the preservation of Balkan unity. He was sent as military attache to Sofia (1934) and Prague (1936), and is rumored to have been connected with underground movements working against Nazi influence in both Bulgaria and Czecho-Slovakia.

In 1939, as chief of Yugoslavia’s fortifications, he revealed himself as a Balkan De Gaulle, holding that a nation of such limited financial means should not try to build Maginot Lines but should concentrate on mobile and offensive possibilities. His superiors opposed him and he was transferred to the military inspection service.

Presently he submitted a memorandum warning that a pro-Nazi Fifth Column threatened Yugoslavian unity and full mobilization in case of attack. War Minister Milan Neditch, now Hitler’s Serbian Quisling, asked Mihailovich to withdraw his memorandum. He refused, and was sentenced to 30 days of military arrest for “disloyalty.” He was freed at the instigation of Inspector General Bogoljub Illich, who is now in London with the Yugoslavian Government-in-Exile.

Sumadija

When Hitler’s Stukas bombed Belgrade on April 6, 1941, Mihailovich had a coastal command in Herzegovina. As the Nazis overwhelmed General Dusan Simovich’s bravely fighting army, Mihailovich retreated eastward into mountainous Sumadija, where Serbia had long fought the Turks. Thousands of disbanded or unmobilized Yugoslavian troops joined him, bringing their arms and equipment. The force was swelled by peasants and mountaineers.

The Nazi press has reviled Mihailovich’s army as “rebels, Jews and Communists.” Unquestionably they are rebels. Unquestionably some are Jews, some are Marxist Communists of one shade or another. Many more, probably, are Balkan “Communists,” which usually means partisans of the country as against the city, the farmer as against the businessman. These people in general have Slavic, pro-Russian (Tsarist or Stalinist) leanings. The United Nations press has often referred to Mihailovich’s forces as Chetniks —the name of a Serbian patriotic body which long fought guerrilla wars against Serbia’s oppressors. Doubtless many are Chetniks or their descendants. But Mihailovich’s army is best described as a patriotic Balkan force, with a majority of Serbs, built around a large nucleus of trained Yugoslavian troops.

In size, in the long military experience of its leader and the great number of its troops, it dwarfs the forces of such historic guerrillas as the Tirolean patriot Andreas Hofer, the Philippines’ Emilio Aguinaldo, and Mexico’s Francisco “Pancho” (“I’ll use the whole ocean to gargle”) Villa.

Stories

Tales about Mihailovich, apocryphal or smuggled out of his mountains, abound in Yugoslav circles. It is said that he has done some of his own espionage, eating with German officers in a tavern where the host, devoted to him, was panicky with fright. Nazi officers are said to have driven up to a farmhouse where Mihailovich and friends were staying. When he had convinced the Nazis of his innocence, one of his friends remarked: “That was a close one.” Mihailovich replied: “It was close for them, too.” He pointed to a bush behind which a guerrilla machine-gun crew had been ready for the Nazis. The General is also rumored to have done a brisk trade exchanging Italian prisoners for Italian gasoline at the rate of one Italian private for one can of gas, one colonel for 50 cans.

Today Draja Mihailovich seems legendary, but he is a legend with a big basis in fact: the fact that he has kept from five to ten Nazi divisions at a time fighting to conquer the country which they destroyed twelve long months ago.

Time Magazine (1942)